The Plessy Decision

While the Declaration of Independence stated that “all men are created equal” due to slavery, this requirement was not established as law in the United States until after the Civil War (and was likely not fully met many years later).Brown v. Board )

- The Supreme Court voted 8 to 1 against Plessy. “The purpose of the [fourteenth] amendment was no doubt to establish the equality of the two races before the law, but, like things, it could not be intended to abolish distinctions based on skin colour or establish the social as separate from politics – equality.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954, 1955)

In the case that became known as Brown v. In fact, the Board of Education named five separate cases heard by the U.S. Supreme Court on the issue of segregation in public schools.

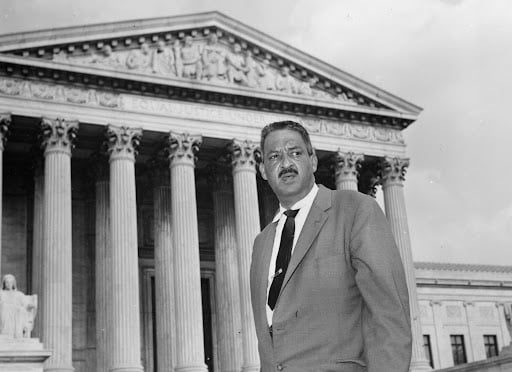

These cases were Brown v. Topeka Board of Education, Briggs v. Elliot, Davis vs Prince Edward County (Virginia) Board of Education, Bolling v. Sharpe and Gebhart vs Ethel. Although the facts differ in each case, the main issue in each was the constitutionality of state-sponsored segregation in public schools. Again, these cases were handled by Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund.

While he acknowledged some of the plaintiffs/plaintiffs’ claims, the three-judge panel of the United States District Court that heard the cases ruled in favour of the school boards. The applicants then appealed to the United States Supreme Court. When the subjects were presented to the Supreme Court in 1952, the Court consolidated all five cases under the title Brown v. England. Ministry of Education. Marshall personally discussed the case in Court.

While this raised several legal issues on appeal, the most common was that separate black and white school systems were inherently unequal and violated the “equal protection clause” of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. In addition, based on sociological tests such as the test conducted by sociologist Kenneth Clark and other data, he also argued that segregated school systems tend to make black children feel inferior to white children, and therefore such a system should not be legally admissible.

When the Supreme Court justices opened the case, they realized they were deeply divided on the issues raised. While most wanted to repeal Plessy and declare public school segregation unconstitutional, their reasons varied. No resolution was found in June 1953 (the Court’s term from 1952 to 1953 ended), and the Court decided to reopen the case in December 1953.

However, within the next few months, Chief Justice Fred Vinson died and was replaced by the Governor. After the hearing in 1953, Chief Justice Warren was able to do what his predecessor had not done, namely.

On May 14, 1954, he issued the Court’s opinion stating, “We conclude that the doctrine of ‘separate but equal has no place in public education. Separate educational structures are inherently unequal.

Pending objections to his sentence, especially in the southern states, the Supreme Court did not immediately attempt to testify for the execution of his sentence. Instead, he asked the attorneys general of all states whose laws permit segregation in their public schools to develop a desegregation action plan. After even more hearings in the Desegregation Court, on May 31, 1955, the judges issued a plan for how to proceed; desegregation was to take place “with all deliberate speed.” Although it took many years before all segregated school systems were desegregated, Brown and Brown II (as the judicial school desegregation plan was called) were responsible for initiating the process.