The history of the Australian Trail

We embark on a 900km, 2-week mountain bike tour of some of Australia trail most epic prehistoric sites: what 20th-century explorer and geologist Douglas Mawson calls “the world’s most epic prehistoric site” The ancient seabed remains of the Great Museum”. Easier access to sedimentary rocks and fossil outcrops.

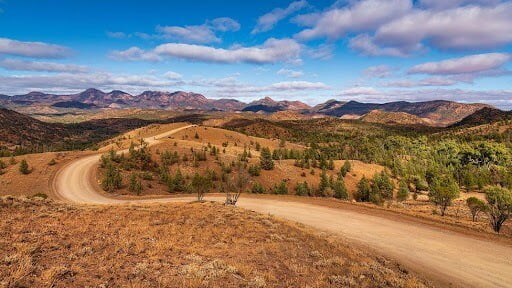

As we drove out of the city and through the crumpled peaks and steep ravines of Icara, Flinders Ranges National Park, a classic example of what happens when two tectonic plates collide over fault lines, the striking kaleidoscopic mountains looked familiar. Their mauve streaks with ridged ridges of orange quartzite have been widely captured by photographers; the iridescent sunrise and the rosy sunset glow were admired in the paintings of such famous artists as Hans Herzen. And the way these chains deformed and rose was immortalized in the creation stories of the traditional guardians of this land, the Adnyamathanha people, for tens of thousands of years.

Did you know?

According to the world’s leading palaeontologists, the 800 square kilometres of the Flinders ranges seem to tell a remarkable story about the dawn of life, a report that forced scientists to rethink the Earth’s geologic time scale.

A hint from the beginning on every sign on the Mawson Trail: an image of a trio of feather-like creatures, a slice of citrus, and a discarded louse exoskeleton. These are the best reconstructions of what life looked like 550 million years ago: soft-bodied flaccid patches (ranging in size from millimetres to over a meter) known as the Ediacaran biota, named after the ancient hills of the Flinders Ranges where they were to find their encrusted footprints.

Of course, this wasn’t yesterday: it happened after the “Snowball Earth” glaciation warmed up and melted, triggering a biological eruption known as the Cambrian Explosion – a relatively short period (15 to 25 million years), fluctuating completely around 521 million years ago. This was when many of the major groups of modern animals, including vertebrates and even the species that eventually learned to ride a bicycle in the mountains, exploded.

We arrived at a red-faced collective stop to rest and check our route, where the Mawson trail randomly intersects with several courses and briefly merges with the Brechin Gorge geological trail (passable). A lone ghost gum sewed a rough rocky peak against an intense cobalt sky. I slowly scanned the sedimentary layers of my throat.

According to Mary Droser, professor of geology at the University of California, Riverside, if you can read, this archive of planetary evolution is one of the best exhibits in the world. “The Flinders Ranges span a huge stretch of time that includes all of the bizarre environmental events that have happened, from Snowball Earth to global warming,” Droser said. “We can see a time window of 350 million years from the microbial world to ancient animal history.” This is because the Flinders’ sorting, subsidence and erosion activity has left the corridors through time layers, revealing evidence of critical epochs and events. One such chapter in Earth’s history was recorded in the western Flinders Mountain Ranges in 1946 when geologist Reg Sprigg was looking for mineral deposits in the low Ediacaran hills.

Sprigg, an avid palaeontologist who had studied under Mawson, brought some soft sandstone slabs and discovered a community of fossil footprints that included five new genera and species. “He knew the ages of older rocks than we know of Cambrian rocks with fossilized skeletons,” said Drozer, one of the world’s leading researchers on Ediacaran fossils. That meant Sprigg knew the footprints were “very, very important,” he said. Sprigg’s discovery solved one of the greatest mysteries in natural science and one that puzzled Charles Darwin for the rest of his life.

When Darwin wrote The Origin of Species in 1859, he emphasized his concern about the sudden appearance of skeletal Cambrian fossils and the challenge this posed to his theory of evolution. He wrote: “… to the question why we do not find rich fossil deposits relating to these supposedly primitive periods before the Cambrian system, I cannot give a satisfactory answer.” This conundrum, known as Darwin’s dilemma, has puzzled scientists for nearly a century. But Sprigg found hard evidence of the loss.

The first complex animal life

Between 570 and 540 million years ago, these hollow forms in the rocks were inhabited by the soft-bodied creatures of the Ediacaran biota, which were one step ahead of single-celled organisms and one step behind animals that ran to eat each other.

The first known complex animal life on Earth. Never before found so many in one place. This discovery revolutionized our understanding of how multicellular animal life evolved. Over the past 20 years, in collaboration with a team led by palaeontologist Jim Gelling of the Museum of South Australia, Droser has unearthed 40 “well-preserved” fossil beds from the ancient seabed Nilpena, a private sheep farm on the western edge of the intervals.

Since then, these cultural relics have become part of the 600-square-meter protected area. The kilometre – roughly the size of Singapore – is called the Nilpen-Ediacaran Reserve. Nilpena is now internationally recognized as the site of the most critical early Ediacaran animal life on Earth and is one of the many reasons why the Flinders Ranges have been declared a World Heritage Site.

Studying several tiny fossilized burrows found at Nilpen in 2005, Droser and evolutionary biologists long ago predicted that around the same time—about 555 million years ago—a creature more complex than another Ediacaran biota was in motion, contracting its muscles during Time travel.

In 2020, using 3D laser scanning technology, Droser and his team were able to recreate the creature: a fat, worm-like mass about the size of a grain of rice. It had a noticeable difference from other life forms that existed: it was the first animal to have a front and back, a mouth, intestines and back – called “bilateral”. This meant that Ikaria wariootia could be an animal that ate and regurgitated during the long transformation that eventually led to humans as they reached the blob.